Rob's Ramblings: The Many Lives of Billy Milligan

Why one serial rapist's story keeps getting told

Daniel Keyes has one of the strangest bibliographies of any American writers. After working as a writer and editor at Atlas Comics, the predecessor of Marvel, and the infamous EC Comics, Keyes wrote one of the most acclaimed and impactful science fiction books ever in Flowers for Algernon, a beautifully-written novel from the perspective of a man who rapidly gains and loses intelligence. After that, he wrote a few books that don’t have Wikipedia pages, but his only other real hit was the journalistic true-crime book The Minds of Billy Milligan.

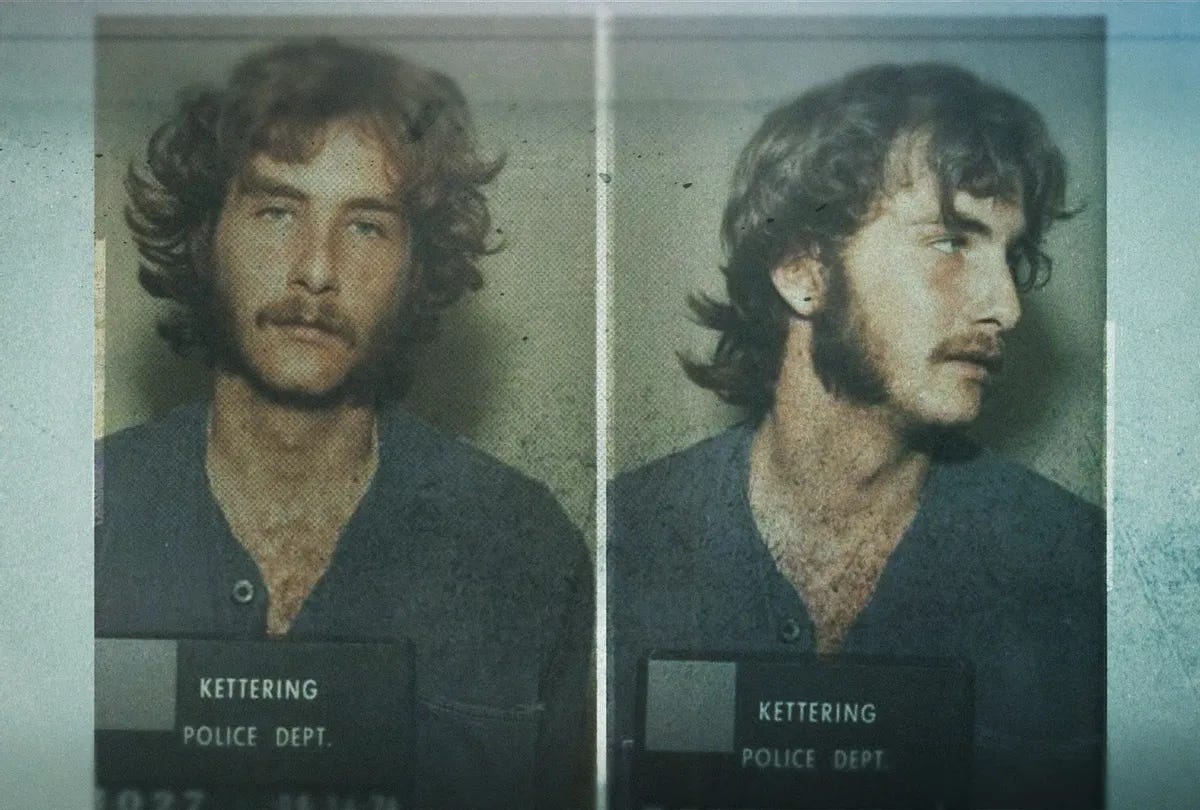

Billy Milligan was a man arrested for a string of rapes and robberies on the campus of the University of Ohio. Once in custody, he claimed to have multiple personalities. Perhaps most risibly from a modern perspective, he claimed his rapes were the responsibility of a lesbian personality who had taken control of his body. Courts found him not guilty by reason of insanity, and he would spend most of the next decade in Ohio’s state mental health system.

The book is strangely structured. The story starts with the rapes, and then goes through Billy’s trial and the beginning of his treatment. Keyes describes his own interactions with Milligan, but in a somewhat elliptical way, often referring to himself as “the author” with a remove that one wouldn’t typically associate with the post-New Journalism era. The rest of the book is then taken up with a novelistic depiction of Billy’s life based primarily on his own testimony, including child abuse at the hands of his stepfather and a descent into petty crime fuelled by “mix-up times” between different personalities.

In a modern true crime story, one might expect the story to revolve around the question of whether Billy is telling the truth: whether his seemingly far-fetched story of having ten (later twenty-four) personalities, mostly broadly-drawn stereotypes, is true or an elaborate con job. One can easily imagine a Serial-style podcast with the host going back and forth on this question. But Keyes seems to have been taken in almost immediately, and writes that all of Billy’s lawyers and doctors have the same experience of instantly believing when he says his personality switches.

Similarly, while Keyes does seem to have interviewed many of the people who encountered Billy, there’s no real discussion of fact-checking his story, which grows more and more elaborate as the novel continues. Billy’s account of his life sounds a lot like one that would be told by a compulsive liar, where the teller is both the most talented and most persecuted person in the world, and any wrongdoing was the result of the wrong personality taking charge at the wrong time.

The rapes, then quickly recede from Keyes’ narrative as it becomes the story of the persecution of sensitive soul Billy Milligan by a cruel and punitive society. At times, Keyes seems to attribute almost supernatural powers to Billy. Conversely, much of the journalism of the period seems to have portrayed the case from a carceral perspective, seeing it as a case of a smooth-talking criminal taking advantage of liberal tolerance.

The Minds of Billy Milligan was published and became a bestseller, but it didn’t do Milligan much good. In response to news of its development, the Ohio state legislature passed a bill to prevent inmates from profiting from selling the stories of their crimes, specifically named after Milligan. The legal wrangling over the money from the book that was supposed to go to Billy would take up the rest of his life. After a judge ordered him to return to treatment a decade after his crimes, Milligan fled the state, travelling around the country and being suspected in at least one murder before eventually being arrested.

After that, public interest in Billy Milligan the criminal began to die down, but the story of Billy Milligan the tortured man with 24 personalities continued to fascinate people. Keyes wrote another book on Milligan, which has only been published overseas for legal reasons. In the 1990s, James Cameron planned to direct a movie based on Milligan’s life starring Leonardo diCaprio, but was stymied by the fact that Billy had already signed the story of his life away to a number of individuals. The project languished in development hell at Warner Brothers for decades, with directors like David Fincher, Gus van Sant, and Joel Schumacher attached, and actors like Brad Pitt, Matthew McConnaughey, and Johnny Depp all approached for the role of Billy.

This project eventually saw the light of day very recently in an almost unrecognizable form as The Crowded Room, an AppleTV+ miniseries starring Tom Holland. Holland plays a heavily fictionalized version of Milligan, “Danny”, who is arrested not for a string of rapes in Ohio but for the much more cinematic and sympathetic crime of shooting his abuser in New York. The series depicts multiple personalities in Fight Club fashion, as friends in Billy’s life that turn out to be imaginary, which is very different from how Milligan described his inner life. The Crowded Room is also one of the biggest victims of streaming bloat, with the revelation of Danny’s condition not happening until seven episodes into the ten-hour season, perhaps accounting for its lacklustre critical reception.

But The Crowded Room is not the only Milligan-related series in recent years. Among the endless tide of Netflix true crime docs is Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan, a four-part series that interviews most of the surviving people important to Milligan’s case. In another typical streaming move, the series uses a lot of unrelated stock footage, corny recreations, and strange camera angles to try to present something visually interesting in a documentary that’s mostly talking heads. Still, it’s probably the most comprehensive and even-handed text on Billy Milligan that exists.

Keyes is presented in the documentary as a somewhat predatory figure, who exploited the controversy around Billy to sell books and didn’t really care what was factual, as is Dr. Caul, who fiercely advocated for the multiple personality diagnosis but was not a licensed psychotherapist. The series also contains a good amount of interview footage of Milligan, both during his treatment and afterwards. Even as the series casts doubt on Billy’s diagnosis, it also revels in the drama of it, featuring moments where the personalities seem to shift. The footage doesn’t have the immediately belief-installing effect that meeting Milligan in person seemed to have, at least for me – if anything, Billy’s mannerisms are a little understated, no matter who he supposedly was.

The documentary, and Keyes’ book, position the debate about Milligan as a choice between two poles: either Milligan was faking the whole thing to avoid prison, or his mind genuinely worked as he described it, with an Englishman and a Yugoslavian having conversations about who should control the body. There is little room for any alternatives – that, for instance, having multiple personalities was a delusion that Billy came to believe in and had to consciously or unconsciously perform, that it was a story absolving him of guilt that had to constantly change and expand. During his rapes, Billy told his victims that he was a member of some sort of guerrilla underground, and the ten-turned-twenty-four personalities may have been a similar delusion of grandeur. Such an explanation seems most likely for me, but I am not a psychologist.

Ultimately, I suspect that the public fascination with multiple personality cases like Milligan stems from our uncertainty and anxiety about our own minds, about all the unruly impulses and thoughts we have, the different sides of ourselves that we show to other people. Wouldn’t it be simpler if all our three-dimensional complexities could be explained as different two-dimensional characters inhabiting the same body, with personalities more like the people we see on TV? Wouldn’t it be better if all your worse actions were done by some other entity?

Billy Milligan’s story changes and morphs to suit the time it is told in. In the long hangover of the 1960s, it was ammunition for the culture war between liberal permissiveness and conservative “common sense.” In the modern age, it’s content: another plot twist in a streaming series, another scandalous true crime doc. Milligan died in 2010, and with him the only person who actually knew what was happening in his mind. But our fascination with mental illness, and the extent to which it can save us from guilt, continue.