It was the end of the war. It was the end of the world.

How beautiful it must have been, to live in those days of total war. To have the world around you bent to one purpose, even a monstrous one. To finally know precisely who the enemy was. This is facetious, of course. For those who lived it, the war was a slurry of boredom, discomfort, and fear. But that these moments have become so iconic, so pure in the Anglo memory, suggests that on some level we prefer physical discomfort and uncertainty to its intellectual equivalent.

But the sun was setting on this era. Everyone knew it. The victory marches were already planned. Eleven days earlier, the United States had dropped a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima. Three days after that, they had done the same to Nagasaki. Those ruins were not yet cold, and the survivors had not yet begun to grasp what had cursed them. On the radio, Harry Truman promised a “rain of ruin from the air, the likes of which has never been seen on this Earth”. It was the rare promise that had already been delivered on.

There had actually been a false start to the postwar celebrations. On the 10th, Japan had offered surrender to the Allies, and this news was meant with celebration in the streets from London to Manila. The Allies had rejected that offer due to the conditions which the Japanese insisted on. They were negotiating from a position of utter strength, and did not need to give concessions. On August 15, as the noon sun hovered over the shattered archipelago of Japan, the empire announced its unconditional surrender.

It was news that everyone anticipated, but it was also greeted with immense celebration across the world. Perhaps for those on the other side of the world, there was a voice in the back of their head confident that the seeming defeat of Japan was false hope, that the war would never, could never end. But end it did, and with it ended the old world, a world defined by empires and the struggle for subsistence. But the new world would take longer to come to some places, and others are yet still waiting.

It was on mornings like these that Sarah Murphy most appreciated being a farmer. For all the potential in the pregnant air, she had no time to sit around the radio and wait. There were animals to feed, plants to water, chores to be done. Even in winter, the farm demanded its share of toil. And when that was over, she had her sewing and her baking. It was not easy to feed a half-dozen girls, a middle-aged husband, and the child inside her stomach.

The farm had become a kind of sisterhood over the past years. With the boys all off in some army barracks, female relatives and two hirelings had pinched in to keep things going. She feared for the boys, but there was part of her that hoped they would stay away just a little bit longer. It was so nice to be a part of the rowdy farmhands’ chat instead of the one on the outside, pretending to be offended. And the women never complained about their portions of food.

Paul hated it. When he was not laying in bed sick, he seemed agitated to be surrounded by so many women. Sarah knew that he fancied Maggie, the scrawny teenager they had hired to till the fields. She could understand why. But his adulterous desire filled him with self-loathing, a quality he had well enough of naturally.

As usual, Sarah began her day cooking up a cauldron of oatmeal. Milly, her husband’s niece (and she supposed her niece too), was at the table reading one of her yellowed paperbacks. Sarah peeked at the cover – Jane Eyre, for what had to be the dozenth time. The radio was playing her favourite station from Sydney, a little choppy but still listenable.

There was music today, which made her happy, particularly that charming American song about the railway. The news was sparse but full of anticipation. Japan would surrender, they were sure of it, but not just yet. There was some business about Swiss cables, reminding her of a classroom note passed from student to student. The whole thing seemed absurd to her. Why were the Japs dragging their feet? Did they not know they were licked? Did they want a third atomic bomb dropped on them?

Paul, like her, greets the end of the war with trepadation. He expresses fear for his friends and relatives working in the Bathurst munitions factory. Will they be out of work when it’s all over? Would any of them know what to do?

Sarah would, at least in the mornings. She would get up, feed the pigs, milk the cow, water the plants. The government had been the most reliable customer they ever had, but she is looking forward to going to market again. It was not as though people would ever stop needing food.

The winter air pricked Sarah’s skin as she walked out to the pigpen. They had one mother, the last of the adults, still nursing her litter. Sarah had named the mother Patricia, although Paul had always said not to name what you were aiming to eat. As she poured food into the pen, Sarah wondered what Patricia would think of all this armistice business. Did animals ever conceive of peace in the endless war between predator and prey?

On August 15, the most popular song in America was “On the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe”. Like most major-label music of the time, it was written by a veteran songwriter – in this case Harry Warren – and given to numerous artists to record, creating the sense that its lyrics were not the product of a singular genius but some ancestral folk song that had only recently broke into consciousness. The version that reached #1 on the Billboard charts was recorded by Johnny Mercer, who had written the lyrics.

Warren had a long history of writing songs for films, which often went on to become pop hits. He provided the music to eighteen of Busbey Berkely’s elaborate blockbuster musicals. This was to be his last real hit, the last song that would hit the top of the charts and win an Academy Award when it was incorporated into the film The Harvey Girls and sang by Judy Garland.

Mercer had grown up obsessed with black music in Savannah, Georgia, an influence he brought into his career as a songwriter. In 1935 he moved to Hollywood, enjoying the experience of working on film musicals but alienated by the luxuries of California. In any case, Mercer was a success, writing hit songs for the likes of Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra and being one of the founders of Capitol Records. Capitol was the first record label based on the West Coast, and by this time was just about up to the same level as the top five record companies. This song, dually mired in the mythology of the West and the world of film, was a representative part of their repertoire. Mercer was not renowned as a performer, but his vocals are capable enough, and it was his version – not Crosby’s or Tommy Dorsey’s, released that summer – that reached #1.

“On the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe” references a real railway company, named after real cities, but the song conjures up something altogether more mythological. The real company never went to Laramie or Philadelphia, but the quietly fantastical one in the song does. Railroads had been a key part of American psychogeography for a over century. They stood first for an unified nation, and then for progress, strips of steel appearing out of nowhere in desolate desert plains to mark the arrival of civilization. In Warren and Mercer’s song, the railway entered into its final significance, as a nostalgic symbol of a vanished age of Western expansion.

Musically, the song is a pop number with cowboy-ish trappings from banjo music to the swing of a hammer on the railway. It offers an easily-consumable version of the West. Americans were addicted to this mythology, showing a seemingly endless appetite for Western movies and dime novels. But perhaps it held especial appeal for a country whose young men were vanished or vanishing to far-away lands. It was easier to imagine them finding adventure back in America, on a train with only one destination.

The Railway, in “Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe”, is all about the normal social circulation of people and things. If it is all about a small-town West, it’s one that resembles a suburban utopia of civility. Where the AT&SF takes you, “folks […] have always got the time of day”, and the passengers have no wilder a destination than “Brown’s Hotel” to rest their feet. People are on the move, but simply to find a comfortable spot to rest. The railway is no longer taking heroes into the unknown: it is a commuter train.

One surprising fact: The AT&SF had once employed a young Harry Truman, who had worked as a timekeeper. Was this, too, a part of the mythic America the song conjured: that the young man riding the rails, sleeping in hobo camps alongside the tracks, could one day be President? Even if it wasn’t, Truman would soon dedicate himself to building exactly the peaceful, sanitized version of Western glory conjured by Mercer, with cozy trains carrying people to friendly tract homes.

It is no wonder that those living in the austere war years fantasized about a carefree, unworried society. And it would be the society they built in the postwar years, one with trains to quiet villages full of pleasant people. The spectral Atcheson, Topeka and Santa Fe was a railroad that lead to suburban conformity. But that was still a long way to come.

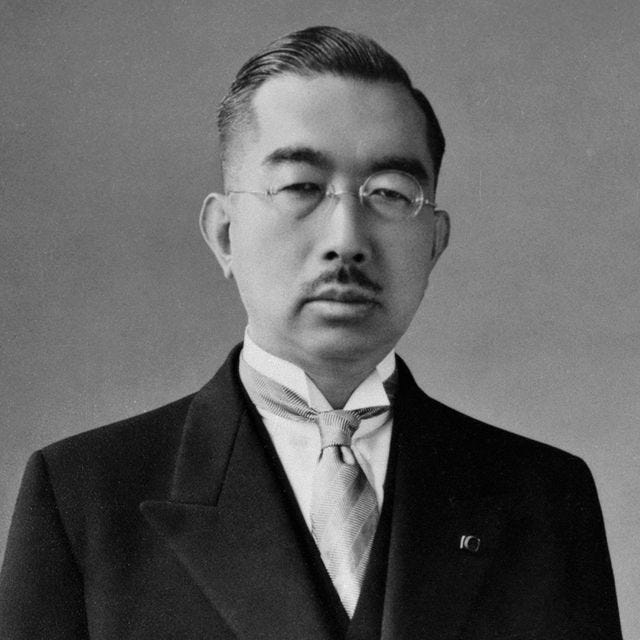

For those who met him, Hirohito seemed less like a god and more like an alien. His skin was papery, his features pinched, and his body thin with the austerity of the war. He had a way of looking just past whoever he was speaking to, or into the middle distance. His lips were constantly pursed, as if he could not breathe through his nose and had to leave a gap for air to flow in.

It had been a long four years. A long twenty years, since he had ascended to the centre of this snakepit. He had wanted to be at a remove from everything, like the kings of England. Let the politicians sort things out while he tended to his plants. But there had been so many hours kneeling in front of generals and advisors, trying to maintain the delicate balance that held up the whole government. He hadn’t wanted the war with the United States, but they had told him over and over again that Japan could win, that they in fact could not survive another five years of peace with the West slowly suffocating them. And he knew better than to resist the military too strongly. He had seen three prime ministers shot down during his reign -- what more would an emperor be? Or so he would maintain, for the rest of his life.

And now, this day. It was a day he had dreaded for three years, and ferverently worked towards for one. It was a triumph, of sorts – the victory of the “peace faction” over the hardliners who wanted to fit for every inch of the main islands. But even the die-hards had been quiet this past week. But if it was a domestic triumph, it was of course also a great defeat, a humiliation on the world stage. They had set out thinking that hey could become a first-class country, stronger than even the Western powers. They had built guns and plains out of the great powers’ stolen fire, but that fire had come back to scorch them.

Two engineers, simultaneously nervous and ashen-faced, had come to his palace with the recording equipment. They were people too ordinary to be here, and that alone had Hirohito nervous. He must put these things aside, he knew. He would not be the same man after this, nor would his people be the same people.

The prepared statement was in his lap, scrawled on the last piece of paper they could spare. The technicians had to tell Hirohito when the microphone was on, then tell him to speak louder. He wondered what they would think of his voice. Would they think it imperial? Would anyone believe it was really him?

As he spoke, Hirohito imagined the men and women that could be listening to him. He tried to give them hope, tried to sound confident as he said that the nation had been defeated but would survive. He imagined children burned by the bomb, soldiers sitting in Kyushu preparing for a battle they could not win, women thin and bony from years of rationing. He hoped his words could inspire as much comfort as fear.

The technicians switched the tape recorder off and left with a polite bow. It would be broadcast at noon. There would be more for Hirohito to do, and an even greater strain – serving the Americans as much as his own people. Or perhaps he could step down, or perhaps he would be tried. That would all be later. For now, it was sunny outside, and his flowers were in bloom, and he could rest for a moment.