Flash-Forward: FLCL Episode 1 - "Fooly Cooly"

Naota makes a new friend

What I watched: The first episode of FLCL, an anime series created by Kazuya Tsurumaki and Studio Gainax. The Japanese voice cast starred Jun Mizuki, Mayumi Shintani, Izumi Kasagi, and Suzuki Matsuo. “Fooly Cooly” was directed by Masahiko Otsuka and written by Yoji Enokido, and was first released as an original video animation on April 26, 2000.

Starring: In the beginning there was Evangelion. Well, in the beginning there was a short film created for the opening of a Japanese science fiction convention, and then somewhere along the way there was Royal Space Force and Gunbuster and Nadia, but it was Neon Genesis Evangelion that made Studio Gainax one of the most famous names in the anime industry. Evangelion is worthy of a much longer analysis, but in short it was creator Hideaki Anno’s attempt at a psychologically realistic giant robot anime, one which eventually became a stark reflection on Anno’s own depression. Despite its troubled production, Evangelion became one of the biggest commercial and critical hits in anime history, and essentially gave Gainax carte blanche for their future projects.

Despite this, the years following Evangelion were not immediately productive for Gainax. While the Evangelion movies were successful, Gainax’s next few TV series included the forgotten Modern Love’s Silliness and Oruchuban Ebichu. Anno worked on the shoujo romance series His and Her Circumstances, but left partway through. He wouldn’t work on another television series again, whether it be as a result of his ongoing mental health issue or simply using the perogative of being a big name to avoid the gruelling work schedule of anime TV series. Everyone was looking to Gainax for the next great anime, but what was the studio without Anno?

Gainax turned to Kazuya Tsurumaki, Anno’s protege, to create a new OVA series. Tsurumaki had been an assistant director on Evangelion, including directing key episodes, but this was his first time helming a series. Tsurumaki would go on to spend most of his future career working on projects linked to Anno, such as the Gunbuster sequel Diebuster and the Rebuild of Evangelion series, so in a sense FLCL is Tsurumaki’s biggest original creation. It’s all the more remarkable, then, that Tsurumaki created something so unique, with shades of Anno’s work but its own distinct artistic sense.

What happened: We open with cryptic dialogue over a modern highway, describing the best way to take a punch. (These lines are taken from Ashita no Joe, a seminal anime and manga about a boxer in post-war Japan.) We soon see this instruction is coming from a purple-haired girl swinging a bat, and talking to a younger-looking boy. She calls him Takkun, and asks him to do her homework. He always carries around a bat, but doesn’t play baseball. The girl gives him a very intimate hug, which he seems uncomfortable with, and bites his earlobe so as not to ”overflow.” We then see the a long shot of the town, including its most distinguishing feature: the factory for Medica Mechanica, shaped like a giant iron and releasing smoke all over the city.

After a brief title card, we are then introduced to a mysterious girl on a motorcycle. Takkun and the girl visit a vending machine, and she gives him a can after drinking have, referencing the famed anime trope of an “indirect kiss.” Takkun throws the can away. This awkard relationship is interrupted by the motorcycle rider, who collides immediately with Takkun. The rider stops the girl from interfering, calling him Taro-kun, even though his name is actually Naota. The rider freaks out , rolling back and forth and motoring around on her knees, before throwing her hlmet off to reveal pink hair and a beautiful face. She kisses Naota, complete with shoujo sparkles, to the other girl’s shock.

We then get a grainy aside with the two women in a bus, complaining about having to do the scene which we’ve just witnessed. A big red X tells us that this is “wrong.” Naota revives under the pink-haired girl ministrations, and she promptly hits him with a guitar, sending him flying. She shakes Naota upside down, with change coming out. She then rides away, leaving the two teenagers in the dust. Despite having a wound on his head, Naota decides not to go to the hospital, and describes the woman as another adult who won’t grow up.

By that evening, the bump has turned into a fleshy protrusion longer than Naota’s nose, but he can suppress it by pushing on it. It doesn’t last for long, though, and Naota turns up to school the next day with a bandage on his forehead. The mysterious “Vespa woman” that Naota has encountered is now the talk of the class. There’s a pun on “Vespa” and “wasp” (which sound more similar in Japanese), and the rumour that this woman “stings” people. Despite this, Naota continues to repeat that nothing extraordinary happens in this town.

After school, our guy finally decides to go to the hospital, only to encounter the Vespa woman again at a railway crossing. She knows that something weird has happened, and immediatley picks up on the bandage. Naota runs away. At the hospital, the nurse tells him that it’s a normal “adolescent skin hardening syndrome”, but it turns out to be the pink-haired woman in a nurse’s office, who goes on a building-shattering rampage with her guitar.

Naota returns home, and we shift to a somber moment, as he remembers his brother, who swung his baseball bat in the same way that the woman did her guitar. That evening, the Vespa woman is at dinner, and finally introduces herself as Haruko, also known as Haruharu. We see this whole conversation narrated in frenetic manga-style panels. She’s now working for the family as a housekeeper. There are references to Yoshiyuki Tomino and his famous Gundam series. Dad asks him about the mysterious “furi-kuri”, which is some sort of sexually charged onomatopeia. Haru says she’s in a relationship with Naota, shocking his father and grandparent.

Later on, Naota is in the bath while Haruko continues to talk to his relatives. He catches her narrating out loud about her plan to take on Medical Mechanica. The two of them are supposed to share a bunk bed. Haruko says that she’s an alien, and again inquires about what’s underneath the bandage. Naota snaps, asking why Haruko doesn’t just harass his dad, and she seems genuinely offended by the question. Naota then claims bottom bunk, confirming that he is a bottom, and relates that his brother (who formerly had the top bunk) has left to play baseball in America.

Haruko also refuses to sleep in the top bunk, so at pain of being molested again, Naota wanders downstairs and has a cryptic chat with his dad about his relationship with Mamimi, the purple-haired girl from earlier. He runs away, and encounters Mamimi on the bridge, smoking a cigarette with an inscription. She’s apparently been waiting on letters from Naota’ brother which never arrive, and eating day-old bread. He tells her to give up, suggesting that the brother already has a girlfriend. Haruko is discovering this around the same time, opening some mail for Naota that has a picture of a young couple in it.

This revelation has led Mamimi to “overflow”, collapsing into the fetal position, and this in turn triggers a reaction in Naota, with his horn erupting from underneath the bandage bigger than ever. It eventually turns into a hand, from which sprouts a human-sized robot with a TV for a head. The robot emerges from its constraints and hauls Naoto up onto the bridge.

From here we enter into a battle scene, with the robot fighting the giant white hand which one held it down. The hand, now resembling a squid more than anything, tries to flee, but the red robot swings it around the bridge and smashes it. All of this happens with Naoto helplessly clinging to the robot, and Haruharu speeding to the scene on her Vespa. She arrives, and drives her guitar into the head of the robot, disabling it. Naota lets out the simplest expression of amazement, “sugoi” and, to his own disgust, thinks that Haru looks a bit like his brother.

The next day, the bandage is gone, with Naota’s forehead smooth and ordinary beneath it. The robot, its exterior coloured blue, is part of the family, helping out in the store, and Naota sees nothing out of the ordinary about this. He meets back up with Mamimi under the bridge, and she offers him a soda. He says he doesn’t like the sour stuff, but gulps it down anyway. That ends the episode, except for the tremendous “Ride on Shooting Star” ED.

What I thought: FLCL is, first and foremost, a singular audio-visual work. The soundtrack, by the Pillows, is an instantly iconic work of Japanese surf-rock, at times underlying the visual storytelling and at time poking its head out to take centre stage, as in the use of “Little Busters” to score the climactic action scene in each episode. Anime music was, at the time, largely instrumentals and operatic anthems that often spelled out the plot of the story. Even Evangelion’s famous “Cruel Angel’s Thesis” more or less fit into the tropes established by 80s mecha anime with its synths and hot-blooded singing. FLCL was noted at the time for “breaking the rules” of anime by including licensed contemporary music as well as the Pillows’ music, which could easily have been played on whatever the Japanese equivalent of a college rock station is.

The events of the animation are almost structured to the music, peaking in intensity when it does. Haruharu’s guitar feels like a symbol of the rock-and-roll cool that infuses the series. The visual style of FLCL also has an almost improvisational feel to it. It’s marked by big, cartoony facial expressions, a willingness to shift between different levels of detail, and somewhat loose lines. The character models and art style shift to depict emotion, building on classic American animation. Anime has never exactly had a realist style, but it does have a kind of default style that is meant to depict the reality of the plot as it exists to the characters without calling attention to itself. This is not the case in FLCL, which is constantly announcing itself as an animated creation.

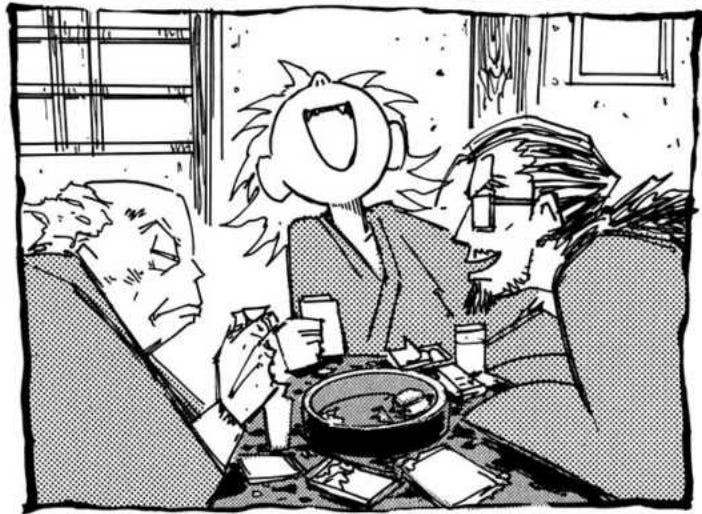

This is nowhere more evident than in the scene where Haruharu meets Naoto’s family. Instead of being traditionally animated, the scene is depicted as a series of traditional manga panels, with dramatic movement of the panels itself making up for the staticness of the image. In a scene that is primarily just dialogue, the viewer is again forced to reckon with FLCL as a hand-drawn (or computer-drawn) object. This effect recalls the nature of anime, which is more often than not adapted from an existing manga series. FLCL was not based on a manga, but perhaps this passage served as a form of promotion for the attendant tie-in comic (more on that later.) The manga sequence also recalls the visual shortcuts used in past Gainax works such as Gunbuster where experimental sequences were used in part to make up for a lack of budget to depict scenes in a traditional way. I don’t think this was a concern in FLCL, which was a limited-run OVA, but it still builds upon the studio’s visual tradition.

All of this visual flash makes the viewer think of FLCL as a conscious invention, rather than a window into an alternate reality, which naturally leads to analyzing the meaning of the story. Here, FLCL also provides a ladder to the inquisitive viewer in the form of a very obvious metaphor. Naoto’s unusual growth, which he tries to hide from his friends but eventually erupts into big trouble, serves as a clear stand-in for puberty. The horn that grows out of his head, as well as the bat and guitar which are used to repel the ensuing monster, are fairly clear phallic symbols. Giant robot anime has always appealed to pre-teen boys, and FLCL makes the link more or less explicit.

Naoto is drawn as the epitome of the anxious pre-pubescent boy, who feels the world growing up around him (emblematized in part by his brother’s departure) but is not yet able to join it. He is defined, in large part, by his relationship with two older, more mature women – Mamimi and Haruharu. He is both attracted to them and intimidated by them, emblematized by the sour soda that Mamimi offers him. This also has a lot of precedent in anime (Misato in Evangelion is, again, archetypal), but also in reality, in those awkward few years between female and male puberty where the girls are taller and more mature and in a different realm than the boys and their still-juvenile pursuits.

And yet, it feels reductive to boil FLCL down to “horn=penis.” There’s something in its strange, almost sleepy rhythm which speaks to the uncertainty we experience long after we’ve grown pubic hair. In their elliptical dialogues, Naoto and Mamimi are always on the verge of reaching some kind of revelation, a breaking point that will allow them to state plainly the nature of their relationship to each other. But they never quite reach it, in the end turning away. So it is trying to apply an interpretive lens on FLCL. After all, as Tsurumaki himself says “comprehension should not be an important factor in FLCL”

Found in translation: As was common with anime at the time, FLCL was conceived as a multimedia project, including a manga series and light novels. Even a relatively small and artsy project had the same kind of production-committee approach as a mecha anime with a full toy line.

The manga was drawn by Hajime Ueda, a doujinshi artist known for his unique drawing style. This is evident in the FLCL manga, which unlike most of its contemporaries is drawn in a very sketchy style with heavy lines and a lack of detailed backgrounds. It almost has the feel of a child’s sketchbook – perfect for the raw, unvarnished experience of Naoto’s experience.

The plot of the first three chapters (or one and two-thirds chapter, as there is a “2-B” and “2-C) mostly tracks with the first episode of the anime series. The story is adapted into a visual medium with reduced dialogue and more extended gags. The puberty metaphor is even more emphasized in this version: we see Naoto’s “bump” as an uncovered, fleshy advantage, and Haruharu and Mamimi make jokes related to sex ed class.

Ueda doesn’t really attempt to recreate the action sequence at the end of episode 1. Instead, Mimi is bombarded with messages in a two-page spread, suggesting that she has a message from “Lord Canti” to “prevent the expansion of Enosville.” We also get a clearer idea of why Naoto is so hesitant around Mamimi, wanting to hide the fact that his brother has a new girlfriend in America. Overall it’s the same story told through a distinctly different creative lens, which is what you really hope for from an adaptation.

TV Guide: For those of an academic persuasion Brian Ruh’s article about FLCL is available online, and analyses the series in light of Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg. I’m not sure how useful this analytical lens is, but there’s some interesting context about FLCL in the history of anime as well as its American release. (I also lifted the tidbit about Ashita no Joe from here.)

Coming up next: Mamimi gets a fun new game in “Firestarter.”