Comics & Literature #2: A Brief History of Comics, Sex and Prestige

How the comics industry went through puberty

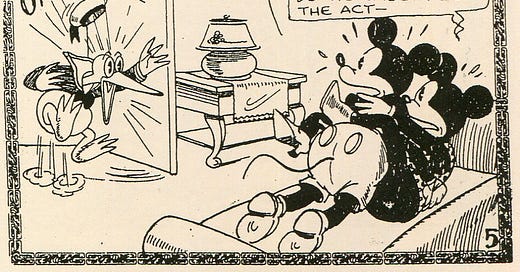

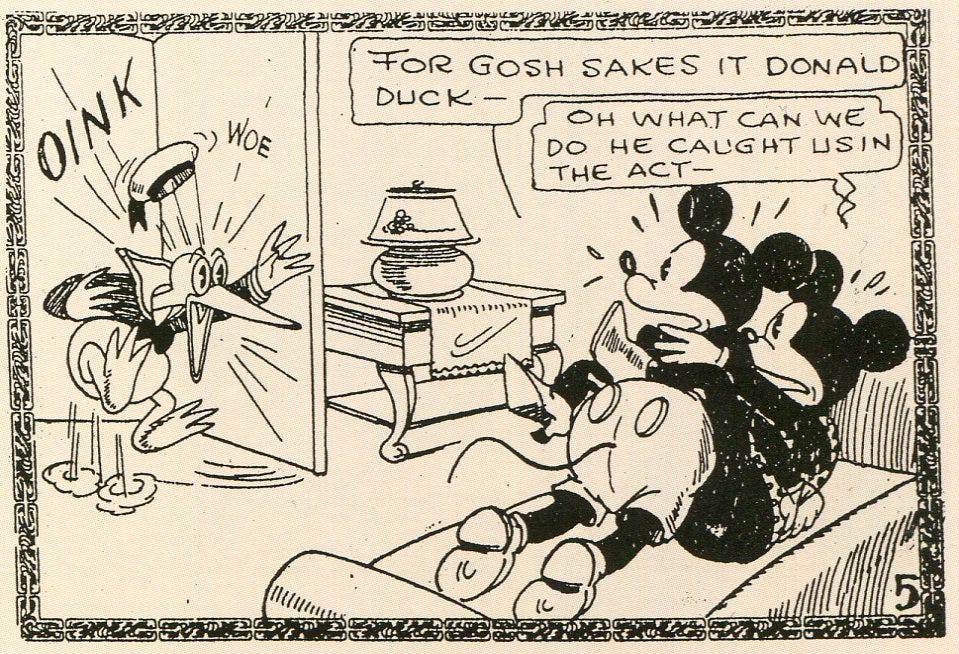

The association between comics and sexual deviance began in the 1920s with the advent of “Tijuana bibles”, amateur pornographic work that often featured celebrities or mainstream comics characters such as Popeye and Blondie. These comics were produced in a clandestine manner and often subject to seizures by police and customs officers, but were printed in large numbers (Adelman). The Tijuana bibles would more or less die out after the conclusion of World War II, but the state’s concern with the potential obscenity of comics would not.

The post-war period saw a boom in the popularity of comics, especially among children. Comics of every genre from funny animal stories to romance flooded drug store shelves (Hadju 6). Amongst these were crime and horror comics, which often featured graphic violence and sexually suggestive imagery. The most famous of these were put out by EC Comics, whose comics like Tales from the Crypt and Shock SuspenseStories attracted a cult audience (Hadju 175-192). Crime and horror comics became the subject of a public uproar, blamed for juvenile delinquency and perversion. Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist, became one of the leaders and the intellectual authority of the anti-comics campaign. In his bestselling book The Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham drew on his work with juvenile delinquents to argue that comics’ use of violent imagery contributed to both violent behaviour and warped sexual development (15). In addition to the lurid imagery of crime and horror comics, Wertham argued that superhero comics such as Batman and Wonder Woman subliminally promoted homosexuality, pedophilia and sado-masochism (34, 189). More recent scholarship, most notably by Bart Beaty, has argued against the common fan image of Wertham as a censorious villain, highlighting his interest in social justice, but it is clear that the popularity of Wertham’s argument raised fears of censorship, as well as a loss of distributors due to controversy, among comics publishers.

As a response to this fear, the major comics publishers established a set of self-imposed restrictions designed to quell public fear (Lopes 54). These regulations, called the Comics Code, would be rigidly followed by comics publishers for decades and formally continued until 2011. The Comics Code effectively banned the horror and crime genres and placed severe restrictions on other types of comics. These restrictions dealt with not just violent and sexual material but the plot and themes of comics stories. Under the Code, "in every instance good shall triumph over evil" and comics were forbidden from displaying "policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions […] in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority" (Nyberg 165). Stories were to emphasize “the sanctity” of marriage, and any portrayal of “sex perversions” was banned (Nyberg 168). In short, the Code demanded that comics abide by conservative morals and offer didactic moral lessons, with one result being the return of superhero comics to their spot as paradigm genre (Lopes 56).

Whatever youthful deviance had been suppressed by the Comics Code would re-surface in the late 1960s in the form of underground comics (or “comix” as they were often called). A group of artists involved in or inspired by the counterculture movement such as R. Crumb and S. Clay Wilson began creating anthologies of short amateur comics that usually involved graphic sex and violence or political radicalism (Lopes 75). Distributed via mail order and countercultural institutions such as head shops, the undergrounds took glee in displaying just about everything the Comics Code was meant to prevent. The underground scene was not, however, welcoming to all. Underground comics frequently included blatantly misogynist and racist imagery, including the work of R. Crumb, the most popular and celebrated of the underground artists (Lopes 82). If underground comix were a celebration of sexuality, that sexuality was entirely heterosexual and male. Artists such as Trina Robbins and Howard Cruse challenged this, creating anthologies for publishing female and gay voices respectively, while underground artists with greater artistic ambitions such as Spiegelman and Justin Green ended up drifting out of the underground movement (Lopes 83). The market for underground comix collapsed in the early 1970s due to fears of obscenity prosecutions and the waning influence of the counterculture, and for a moment it seemed as if the squeaky-clean monoculture of Code-approved comics had won (Lopes 86).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Eternal Couch Potato to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.