Comics and Literature #1: Introduction

Author’s note: This started life as my PhD dissertation, so it has a much more academic-y tone than most of my writing, although still perhaps not academic-y enough for the academy. As such you’ll see a lot of in-text citations and perhaps more deliberateness than my other work. Hopefully this will still be interesting to some.

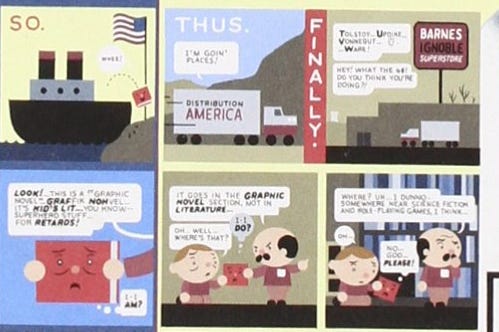

Chris Ware dramatizes the hopes and anxieties of the alternative comics creator in the mainstream book market on the back cover of the paperback edition of his graphic novel Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Boy on Earth. This miniature comic narrative situates the graphic novel in a very specific commercial and cultural context. An anthropomorphized version of the book is about to be shelved in the literature section of a book superstore, cementing its place in the literary canon :“Tolstoy... Updike... Vonnegut... Ware!” (Ware bc). An ignorant sales manager intervenes, and insists that it should be shelved in the graphic novel section (“somewhere near science fiction and role-playing games, I think”) because it is “kid's lit... you now... superhero stuff... for retards!” (Ware bc). Separated from its true literary audience, the graphic novel is neglected and thrown out, only to be rescued by Ware himself. Questions of shipping, distribution, and marketing, the mundane business transactions that the autonomous author is supposed to be disdainful of, are here positioned as vital to the work’s identity.

This comic is obviously tongue-in-cheek and could be dismissed as a throw-away gag, but in the process of being flippant Ware hits on the hopes and anxieties that drive much of alternative comics. The ambition of Ware’s graphic novel, as expressed by the back cover, is not to be acclaimed within its own subculture but within the cultural economy of literary fiction, with Tolstoy and Vonnegut forming more logical antecedents then Lee and Kirby. The back-cover narrative is also noteworthy because the specialized comic book store, where Ware’s book would presumably face unimaginable indignities, is never mentioned. Indeed, from its bookstore-ready size to its baroque instructions on how to read a comic, the collected Jimmy Corrigan is a comic that obviously aspires to an audience that does not normally read comics.

How did such a paradoxical bit of marketing come about? It is not that Ware is a snobbish outlier among alternative comics artists. If anything, he is among the least obviously “literary” of the major figures in contemporary comics, being more obviously influenced by graphic design and the eccentricities of turn-of-the-century print culture than literary fiction (Bredehoft, “Comics Architecture” 884-885). But he nevertheless promotes a discourse that positions acceptance by the literary sphere as the natural aspiration for comics creators who have ambitions beyond the commercial. Graphic novels are now sold in the same stores as literary novels and reviewed in the same publications. Those within both the comics sphere and mass media present this as the maturation of the medium (Pizzino 1). Comics, having passed through decades of juvenile adventure narratives, have finally reached their full potential of being heavily-illustrated novels. This assumption is embodied in the very phrase “graphic novel,” with the novel as the central noun being modified. This is a term that has been used by alternative comics artists since the 1970s and popularized by Will Eisner as an expression of literary ambition as much as format, and been criticized by some scholars as an appeal to the authority of another medium (Weiner 6). By comparison, Scott McCloud’s preferred term of “sequential art” (5) is almost never used by publishers.

I do not believe this paradigm to be a betrayal of comics, nor do I wish to denounce those who created and advocated for it. The emergence of comics-as-literature has brought a broader array of readers and writers into the medium and produced more diverse and frankly more interesting work than the continually-shrinking cloister of the direct market. But it is not a natural endpoint for the comics medium, nor is it an entirely organic outgrowth of the autonomous desire of creators. The comics-as-literature paradigm was produced by a variety of actors, including authors but also critics, editors and booksellers. These actors saw the advancement of the medium as synonymous with entry into the mainstream literary field, a belief that certainly had its pragmatic justifications but also reflected a credulous faith in that field as a guarantor of respect and artistic autonomy.

Entering the world of the book – from stores to libraries to reviewers – was a way for comics to become a true art form instead of low-cultural detritus. This assumption has been reproduced in many histories of comics, from the simplified “comics aren’t for kids” narrative in the mainstream press to academic works such as Paul Lopes’ Demanding Respect which describe the dawn of alternative comics as part of a “Heroic Age” in which creators asserted their rights (121). It is undeniable that alternative and literary publishers have offered writers and artists more liberty in terms of subject matter and style than Marvel and DC did. But the association of the literary with artistic merit occurs in comics discourse from at latest the mid-1970s, a full decade before said literary world would give comics the time of day, and anxieties around the literary continue to proliferate in contemporary comics texts and para-texts. Even when such a project appeared idle fantasy, it still had a grip on the imaginations of comics creators and fans. It is the purpose of this work to examine the way in which the comics-as-literature project was created and argued for by writers and critics, and to highlight the ideological underpinnings of this project.

Those arguing for comics-as-literature were influenced by a variety of literary works and artistic and political beliefs, but there are surprising commonalities between their arguments. One trope that continually reoccurs is the discussion of the comics medium’s literary development in a psycho-sexual register. Comics achieving literary maturity is repeatedly portrayed as akin to the individual achieving healthy sexual maturity. What constitutes sexual maturity varies widely in this discourse, from Dave Sim’s misogynist vision to the anarchist sexual politics of Alan Moore to the queer exploration of Alison Bechdel, but the implied parallel between sexual maturation and literary development remains a constant. In turn, the prolonged immaturity of comics seen in its investment in repetitive and corporate superhero fantasies is depicted as a form of sexual deviance and maladjustment.

The investment in metaphors and narratives of maturity and growth is an example of what Barbara Hernstein Smith describes as the “developmental fallacy”, the concept of a life’s progression from undeveloped and childish tastes towards mature appreciation of greatness (79). If comics were only for children, this view would suggest that they were less developed than adult-oriented literature, and hence adult-oriented comics were necessary to advance the medium. These “adult comics”, to use Roger Sabin’s term, suggested the attainment of maturity on the part of not just the reader but also the artist, as suggested in graphic kunstlerromans like Fun Home, and the medium itself (Sabin 3.) The fixation on literary “adulthood” has lead to an ongoing marginalization of children’s and young adult comics within comics criticism, even when these comics share many of the aesthetic and narrative techniques of adult-oriented alternative comics (Beaty and Woo 103). The developmental narrative has, as Christopher Pizzino has argued, remained one that marginalizes comics, with many educational institutions still viewing them as part of a developmental arc that will lead eventually to a mature appreciation of prose literature. Nevertheless, this developmental narrative is one told over and over again by creators and critics within alternative comics.

If the maturity of “adult comics” is the mark of a successful developmental one, the mark of a failed one is not just immaturity but perversion. The prolonged juvenility of the comics medium is frequently and rather alarmingly associated with rhetoric of sexual deviance or predation. The root of this anxious intersection can be traced back to the public outcry against indecent crime and horror comics, and the subsequent Comics Code which censored any trace of sexual or deviant imagery from comic books. As Joe Sutcliffe Sanders has argued, any analysis of sexuality in comics has to be informed by this history of suspicion and censorship (161). Bart Beaty has productively placed the 1950s comics scare into the intellectual context of the mid-century critique of mass culture, a critique that described comics, along with other mass media like television, as brainless and harmful to American culture. Beaty’s reading of Fredric Wertham’s accusations against comics reminds us that comics lost their chances at sexual expression and artistic legitimacy at the same time, and that attempts at artistic comics would have to grapple with both halves of this legacy.

This is not to say that all reproduced the homophobic aspects of Wertham’s arguments. Authors such as Alan Moore and Alison Bechdel have done their best to reclaim this image of the deviant, comics-addled youth – but even so, the image persists. Intersecting narratives of sexual and literary development became a way for alternative comics creators to figure out their own place in an increasingly muddled cultural hierarchy. For this reason, examining how alternative comics treat literature and sex, and especially how they treat the two in conjunction, provides a glimpse at the changing aesthetics and ideology of alternative comics.

What I will suggest, then, is that the discourse around artistic development within alternative comics is constantly and hopelessly intertwined with a more metaphorical narrative about psycho-sexual development. The putative goal of the former is to dispel the latter, to assert that Wertham’s historic claims about the perversity of comics were unfounded. But the maladjusted and deviant comics reader, to say nothing of the cynical smut-peddling comics creator, constantly returns to haunt alternative comics, often making its way into the very arguments of those seeking to legitimate the medium. These contradictions become most apparent when literary texts and figures, or just an abstract idea of the literary, are invoked. Literature, in the most polemical versions of the developmental narrative, is the horizon of maturity towards which comics must travel.

However, which literary texts should be emulated, what that maturity will look like, how comics should approach this pole, and whether such a voyage is even possible are subjects of dispute between authors of alternative comics. The figure of the literary is one that is constantly contested and used to make competing ideological and aesthetic claims. Even later alternative comics which call into question the developmental narrative, such as Alan Moore’s late work, still make claims about literature. So, rather than suggesting one monolithic developmental arc to which all creators adhere, I suggest that there are many competing and contradictory versions of this basic narrative, all of which are a means of contesting value within the sphere of alternative comics. The arc of literary development, then, becomes a way of uncovering aesthetic pressures and ideological fissures within comics history.

Works Cited

Beaty, Bart and Woo, Benjamin. The Greatest Comic Book of All Time. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Beaty, Bart. Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture. Jackson, UP Mississippi, 2005.

Bredehoft, Thomas A. "Comics Architecture, Multidimensionality, and Time. Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth.” Modern Fiction Studies Vol. 52, No. 4, 2006, pp. 869–890.

Lopes, Paul. Demanding Respect. Temple UP (2009).

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harper, 1993.

Pizzino, Christopher. Arresting Development: Comics at the Boundaries of Literature. University of Texas Press, 2016.

Sabin, Roger. Adult Comics: An Introduction. Routledge, 1993.

Sanders, Joe Sutcliffe. “Theorizing Sexuality in Comics.” The Rise of the American Comics Artist, ed. Paul Williams and James Lyons, UP Mississippi, 2010.

Smith, Barbara Hernstien. Contingencies of Value. Cambridge: Harvard UP (1991).

Ware, Chris. Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Boy in the World. Pantheon, 2000.

Weiner, Stephen. “How the Graphic Novel Changed American Comics.” The Rise of the American Comics Artist, edited by Paul Williams and James Lyons, UP Mississippi, 2010, pp. 3-13.